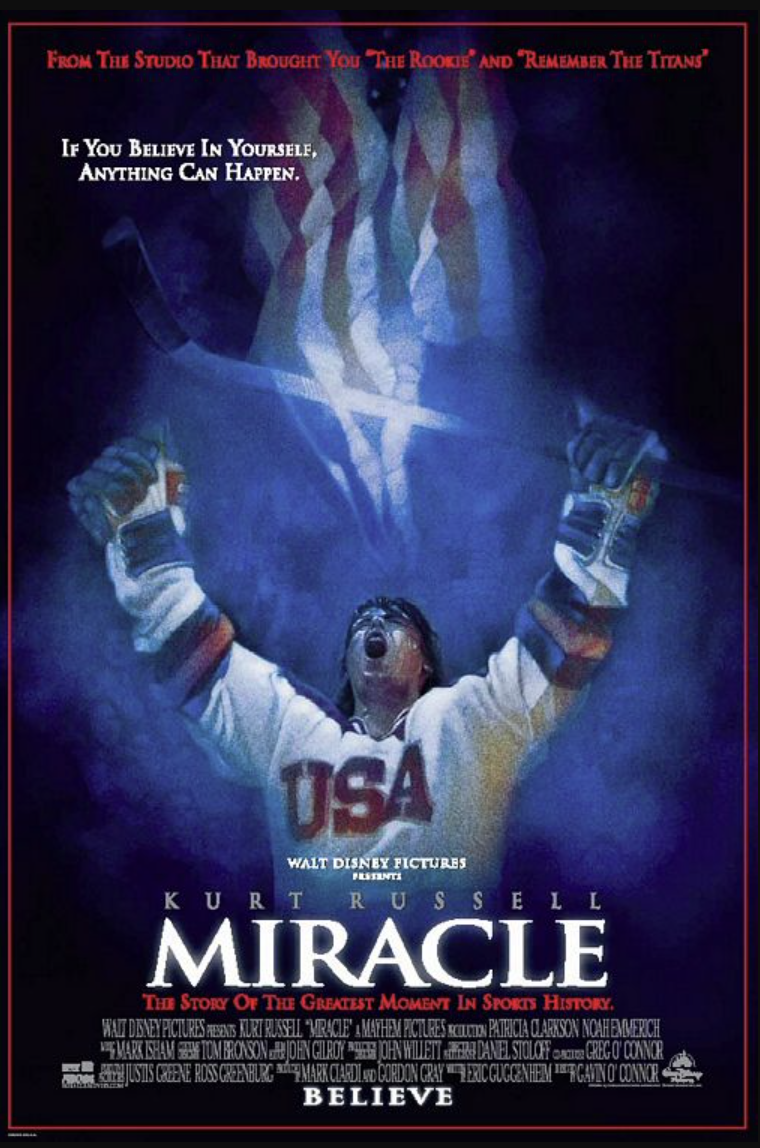

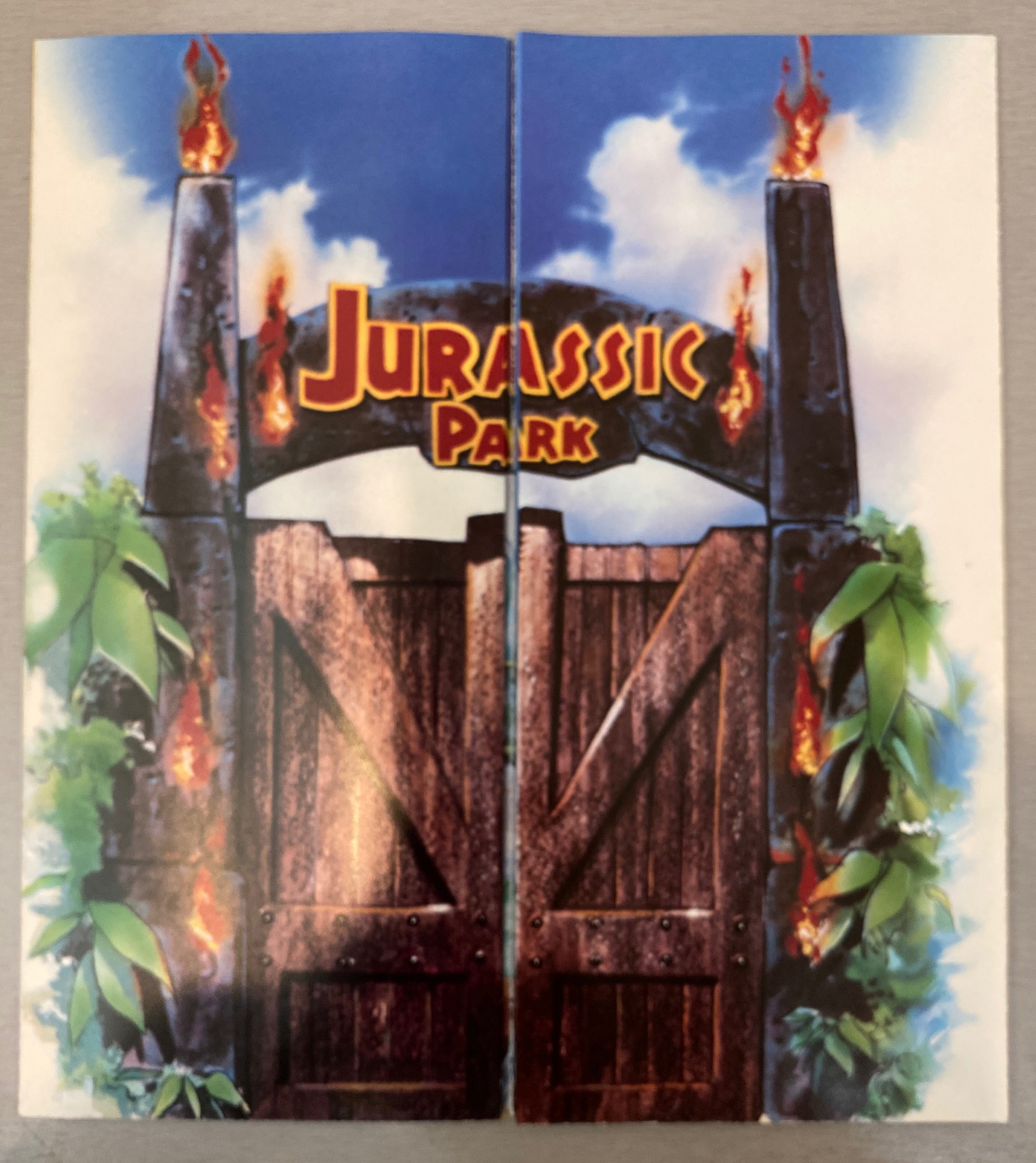

We have loved John Rowe since, well, forever. He has the incredible talent befitting a man with his impressive CV. He’s a movie artist with several high profile images including the poster for Miracle, and a screen-used brochure for John Hammond and his company InGen’s Jurassic Park. He’s an illustrator who learned from some greats like the legendary Saul Bass and created murals featured at Disney World, and is a fine artist who finds the layered meaning in whatever he paints. He’s also gentle, deep soul who infuses those qualities in his work, and takes every project to heart, be it a corporate commission, Disney fine art, or the portraits he creates of people he finds compelling.

In the span of time we’ve known John, we’ve become friends, and seen him create some beautiful Disney interpretive art, as well as lean into his fine art portraiture. He’s won some of the major illustration and fine art awards, while always maintaining his realistic yet emotionally evocative style. We’re thrilled to be able to offer the John Rowe Disney Fine Art Archive Editions Collection, all from John’s personal collection of Artist’s Proofs. In honor of the release of this collection, we interviewed the artist about his career, aesthetic, and where he gets the great ideas on which his most popular Disney images are based.

Leslie Combemale: What were the early indications when you were a kid that you wanted to work as an artist?

John Rowe: I used to draw every single day of my life. Even when my friends would come over and want to play, I would have to say, “Well, let me finish my drawing, and then I’ll go play football.” I just always loved drawing. When I was in elementary school, I wouldn’t fill out the papers they kept passing out to me, asking questions about dinosaurs or plants or whatever it was we were studying. Instead, I would draw a picture of them. So I would draw that dinosaur, or shark, or plant, I’d draw them perfectly with every fin and every element exactly. And then instead of turning in the work that the teacher had been passing out, which I thought was very boring, I would walk by her desk, and I would nonchalantly flip my drawing on her desk, because I wanted her to know that I was keeping up.

You were like an illustrator and training! Did you get good grades?

No! I was failing. And I was going to fail second grade. Then we went to a meeting with the teacher and my mom, and it wasn’t until then I figured out those papers are what they care about in school. I thought, “That is so weird.”

So you’ve always gone your own way, which is so important for an artist.

You have to kind of have your own agenda and your own vision of what you want to do, and then how you want to live your life.

How did you wind up at one of the most prestigious art schools in the world, Art Center?

I was going to become a history teacher, because I tested really high in history. But when I got up to Cal State, I couldn’t go through with it. So I told them I wanted to be an art major, and they told me I had to have a professor in the art building sign off, so I went to the building, and it was five stories tall, but there were no professors there because the semester hasn’t started. So I’m wandering around, and I run into Al Fiore, and he says, “I’ll sign this for you If you take my class.” I said, “Well, I can’t take your class, it’s an upper division class, and I’m just starting.” He said, “Just take my class.” So I take his class, and he also teaches at Art Center. He’s also a designer designing the new interior for the L 1011 airplane and the cockpit for some new Boeing airplanes. I turned on my first project and he says, “If you graduate, after four years here, they will never teach you to be better than you are. Let me help you get into a real art school.” And then he helped me get into Art Center.

Explain who Al Fiori is, explain the importance of him as an artist.

He was a designer, and he taught at Cal State, LA. He was the head of the design department there, and he also taught at Art Center. He mentored so many people. I hooked up again with him years and years later, just about 15 years ago. He said he got asked to take a sabbatical from Cal State LA because he was cherry picking all of their very best students out of the school art and sending them to Art Center. He said, “I had just been offered a job at NBC to do some design work for them, and as part of the job, they gave me a Ferrari. So I parked my Ferrari out at the loading dock, and I was interviewing with the dean of the school, who told him to take the sabbatical, and to reconsider not pinching students, and he could come back later. They said they’d pay for my year off. And I said i’m out of here, Just then the guy from the loading dock came in and said, ‘Hey, somebody’s Ferrari is blocking the loading docks. Anyone know who’s that is?’ And I said ‘That’s mine. Gotta go!'” He said that was the best exit he ever made in his life.

That’s a great lesson that it’s possible to be an artist and make money at the same time. You worked with one of the greatest illustrators in film history, Saul Bass. Can you talk about that experience and what it taught you?

I learned a great deal from him. He was incredibly meticulous. Everything had to be perfect. I had worked for months on the color for the Japan Energies logo, and he had done hundreds of drawings, and I was just painting color. I had two 8 x 8 inch pieces of art that I had made, and each one had to be identical. So the Japanese CEO would come in with his entourage, there’s about 15 people in the studio. And Saul and everyone is there, and they have my art, and they’re dropping a jeweler’s loop on it, and going over every every part of both pieces. They found a difference between the two. And they’re freaking out. “One piece has to go to Japan, and one has to be here. We need to be able to print worldwide from these two things.” They were busy on the phone trying to get a first class ticket to fly my art, because the CEO of Japan Energy was leaving in a few minutes, and it had to be fixed. My art couldn’t go by FedEx or any other way, it had to be hand-carried to Japan. So I hear them on the phone, and they’re asking if I can fix it in the few minutes before the CEO leaves. Yes! Yes, I can fix it!” And I’m in my mind, I’m thinking that first class ticket is the same price and the fee they’re paying me!.

He didn’t deal directly with you, right?

Normally, no. One thing about Saul is, I did 30 projects for him. I would go in with the team of designers. I would be sitting there, and he never talked to me directly. He always told the designers all the notes and fixes needing to be done. I was just the hired help. Then one day, I had messengered a little oil painting over there, and he was sitting there, again with the designers there too, ripping my newest assignment to shreds, saying how pedestrian it was, and how it looked like what some shlock illustrator would do, then he looked directly at me. It was the first time he had ever spoken to me, and he said, “Nice painting yesterday.” He ripped the one I was there for to shreds, but the one from the day before he liked enough to compliment me.

That’s when you know they mean it!

When Saul did pass away. all Hollywood was going there because he had done so many film projects and so many things, and Walter Matthau was speaking at the eulogy and stuff like that. And Nancy, his project manager, called me up personally and said, “Hey John, I know Saul would have liked it if you were there, so your name will be at the door. Just come. It would be good.”

You’ve worked on some pretty high profile projects some folks don’t even know about. You’re full of stories!

I have a story about the day I didn’t meet Steven Spielberg. I was working for a designer friend of mine, and I was painting these gates, and I was up all night doing it. I have a story about the day I didn’t meet Steven Spielberg. I was working for a designer friend of mine, and I was painting these gates, and I was up all night doing it. I mean, literally, I got the assignment and I had to stay up all night. So I came in with no sleep to the Universal to a place I didn’t know, because I don’t follow movies, called Amblin Entertainment. I delivered this thing, and the guy at the desk says, “This is great. It’s wonderful. This is really cool. Steven will love this. Steven will think this is really nice. I can go back and show Steven, do you want to meet Steven?” I’m like, “No, man. Just show him the work. I’m so tired.” He goes and comes back and says, “Steven loves this. Steven wants another one tomorrow.” I go back home, and I tell my wife, “This guy I work for is just obsessed with his boss. He must have said the name Steven 100 times.” and she asks, “Where were you? Do you have a card?” I pulled out a card and I gave it to her and it said “Jurassic Park”. She said, “Do you know what the biggest movie next year is going to be? Jurassic Park.” I did a brochure for him for that, and it was used in the movie.

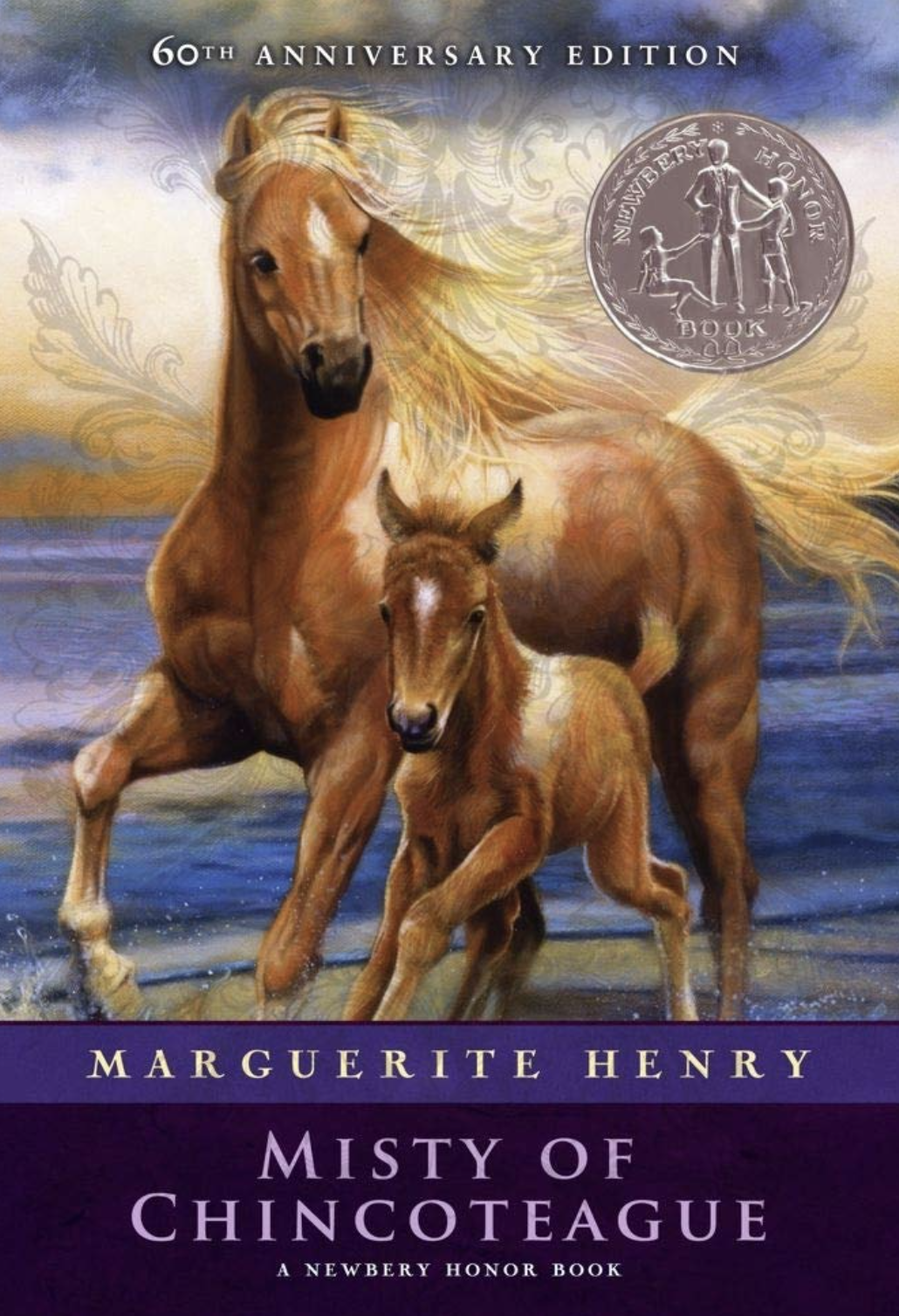

So in terms of projects that you’ve done that had a huge impact on your forward movement as an illustrator, what are a few? I know creating the covers for the reprinted Marguerite Henry books Misty of Chincoteague, that was a big deal.

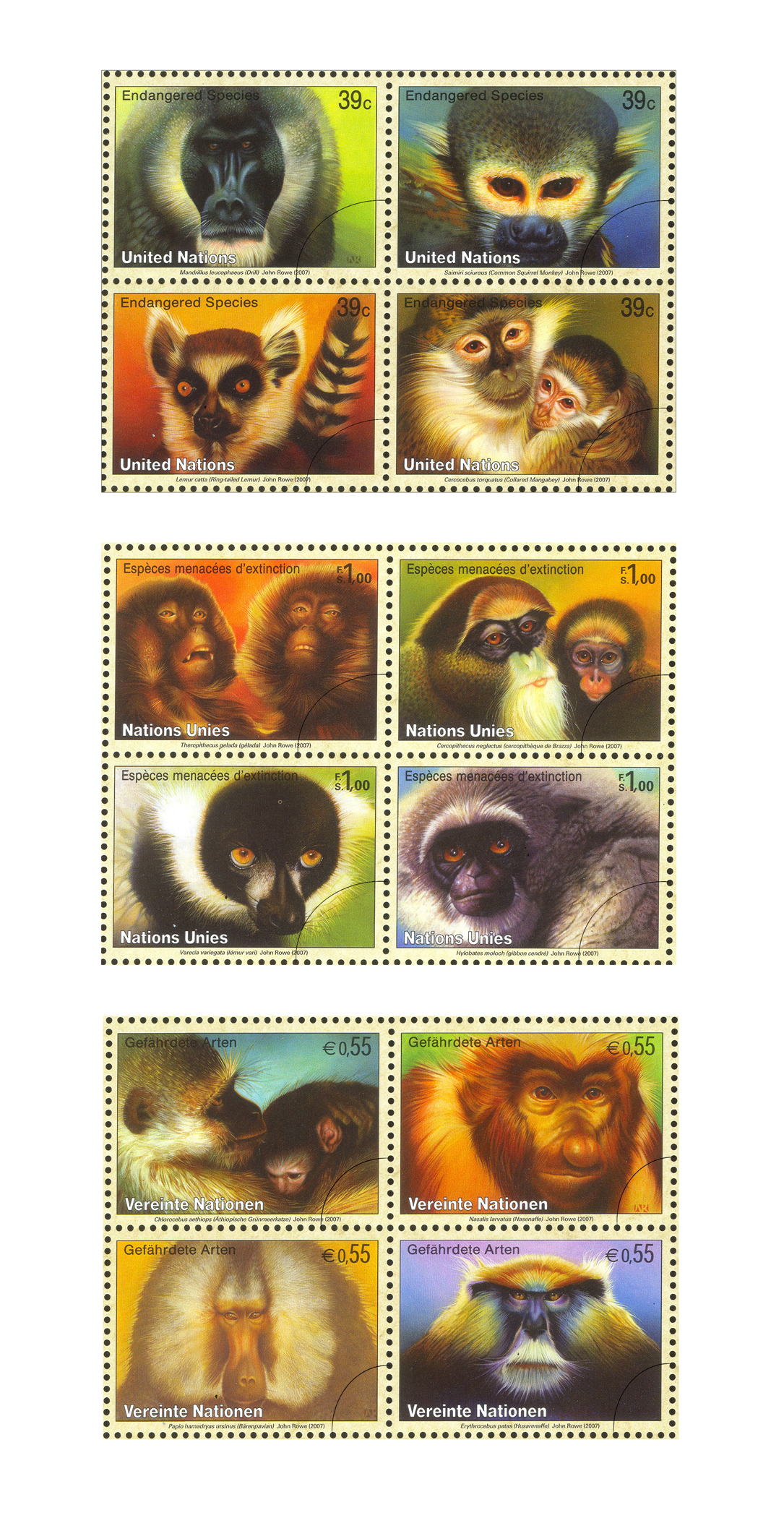

I think those books were really important. Also one of the high points of my career was when I got a commission to do 12 stamps for the United Nations. Once you get a commission from them, they let you do anything you want. They don’t give you any direction, they just trust. Then once I delivered them I was able to go to New York and speak at Madison Square Garden and signed my autograph to hundreds of people’s first edition stamps. I was able to take my daughter, who was 17 years old at the time, and she got to see her dad do something cool.

You’ve also done a lot of images for Disney, some of which people see every day.

There’s a big mural in Animal Kingdom Park at the entrance. It’s 80 x 20 feet tall. When I did that mural, the director called me in, and she had a beautiful little drawing she’d made of all these animals. She said, “I hired two artists and both did a terrible job. We didn’t go forward with them. I’d like to do the same with with you. I’m gonna blow this up to eight feet and then you can paint on top of that.” I looked at it and it was a nice drawing but not the kind I’d need to do a photorealistic painting, so I told her “I’d love to do that, but I can’t work on paper, so I’ll transfer it to canvas myself and then I’ll do a sample of that.” Then I corrected all the things that needed to be fixed and perfected and did the sample and she loved it. You can see those murals today at Disney World.

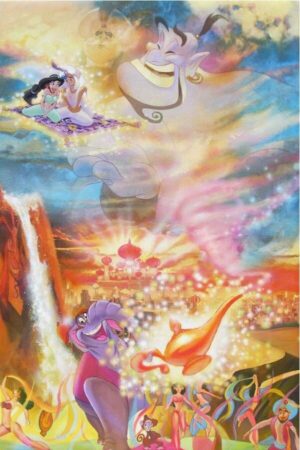

You’ve done some really beautiful images in your partnership with Disney fine art. What was the inspiration for kind of that aesthetic?

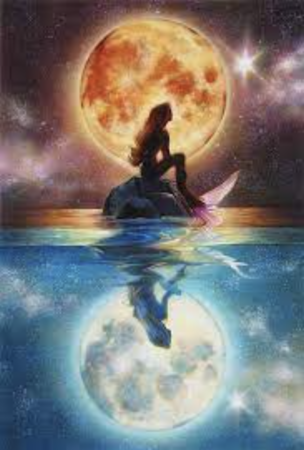

The stories that Disney tells, I think they touch us. We’re influenced by them because they really relate to real life. When I painted a Disney story, that’s what inspired me. I had one that’s really personal to me, The Little Mermaid piece called “Fathoms Deep”, and when I painted that, Ariel is dreaming about a better life like a real person would, and just below her I had the good fish, and deep below I had the monstrous fish.

I painted them looking very realistic, but very evil. And I met a young woman who was 20-something who had that image tattooed on her leg. She came to me and she said, “This is my life. I grew up in gang violence, my parents were murdered when I was young, and I was raised around some bad people. And I’m that little girl wishing on the star, and wishing for a better life. And below are represented all of the gang violence and all of the things that I came through and I got out of in my life. That really made me understand how these stories, although they’re animated cartoons, have a real life story, a resonance within them that’s deeper than that. So I wanted to paint realistic figures, realistic people, and realistic scenes, because I think our emotional experience of these animated films is not the experience of a cartoon, our emotional experience is experience of how real people live life.

That desire to connect, to speak to real life experience, extends to your other fine art.

I do feel the same way about fine art. I don’t want to just do a nice, pleasant painting, I want to do something that speaks to something deeper about the model I’m painting. Almost all the models I use are people that I meet, and then I photograph them and talk to them, and find out something about them. That way, the painting can have some relation to the kinds of experiences they’ve had in their lives, but also that the viewer can relate to and find inspiring in some way.

You can see all of his Disney work on our website HERE. You can see his fine art on his website HERE.