When a future sci-fi classic and an sci-fi-loving art geek collided

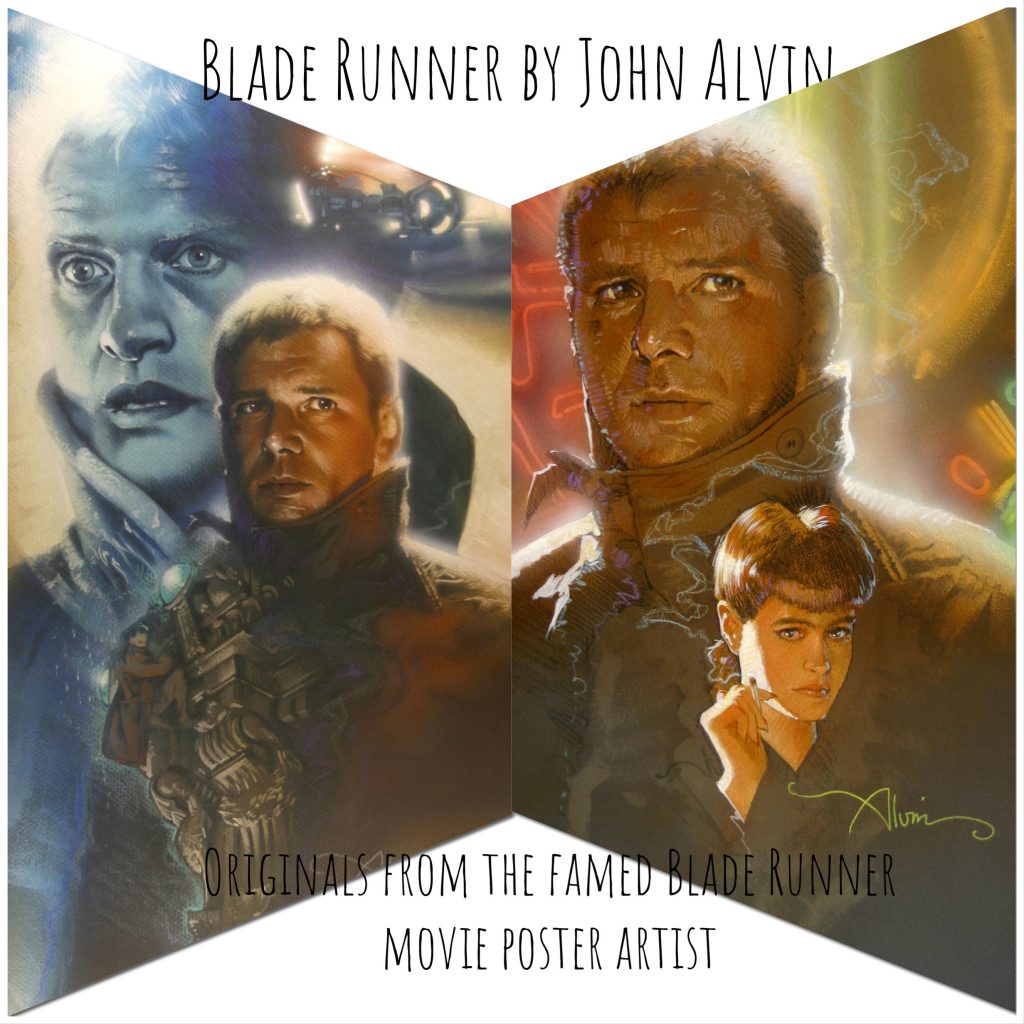

ArtInsights Gallery just got the last two original paintings representing Blade Runner created by the campaign artist who designed and painted the official movie poster in 1982. John Alvin is the illustrator for the iconic image used to promote what would become one of the classics of the science fiction film genre. He made only a few paintings featuring the characters from Ridley Scott’s film, and we can now proudly say we have or have sold every one of them. The last full color mixed media images of Blade Runner art are in the gallery right now.

A DUSTIN HOFFMAN DECKARD?

Imagine Dustin Hoffman as Deckard. It’s hard to do, and yet, he was one of the major actors not only considered but attached to the film early on. Also in play were Paul Newman, Al Pacino, and Gene Hackman. When Hoffman left the project over artistic differences, the filmmakers settled on Harrison Ford, who was just finishing Raiders of the Lost Ark at the time.

JOHN ALVIN & RIDLEY SCOTT SHARED A LOVE OF ARCHITECTURE

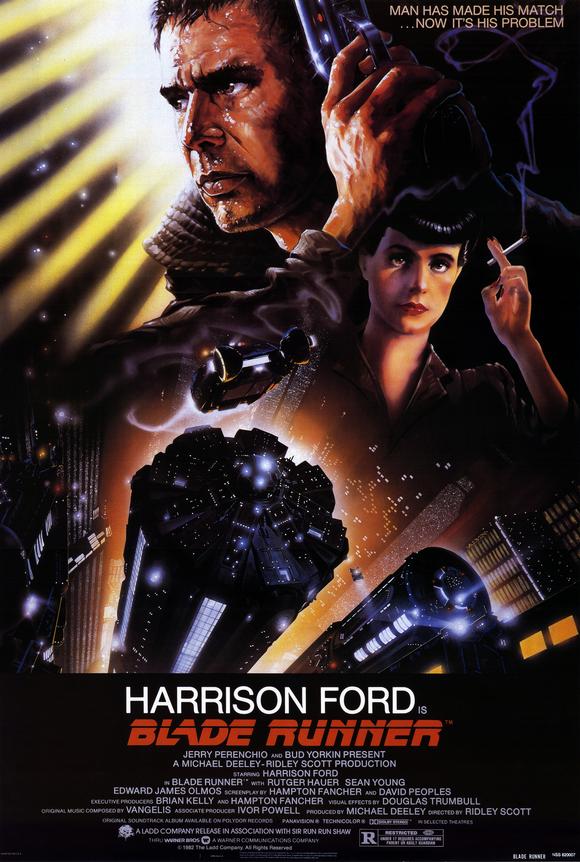

John Alvin wasn’t the first choice to make the movie poster, either. It’s not that they had someone else in mind, but rather, that the marketing folk had ideas they wanted to use. Alvin was in on an early meeting that included Ridley Scott, at which point he told Scott that he thought the architecture was really important to the poster and needed to be a major feature. Scott stopped what he was doing and saying and turned to John Alvin, asking him to explain what he had in mind. He explained what he had in mind for the poster, which would include Harrison Ford as Deckard, replicants Roy Batty and Rachael, with the architecture and gear featured in the film figured prominently. He would use what he called “heavy light” (what Disney executives would later consider part of “Alvin-izing”) to add a bit of film noir atmosphere. Though ultimately Roy was not part of the key art for the movie poster, the rest of John’s ideas can be seen in the famous finished poster image.

He would revisit the idea of Roy Batty as an essential part of the poster later, when he created an anniversary image that made Roy the dramatic central focus of the art.

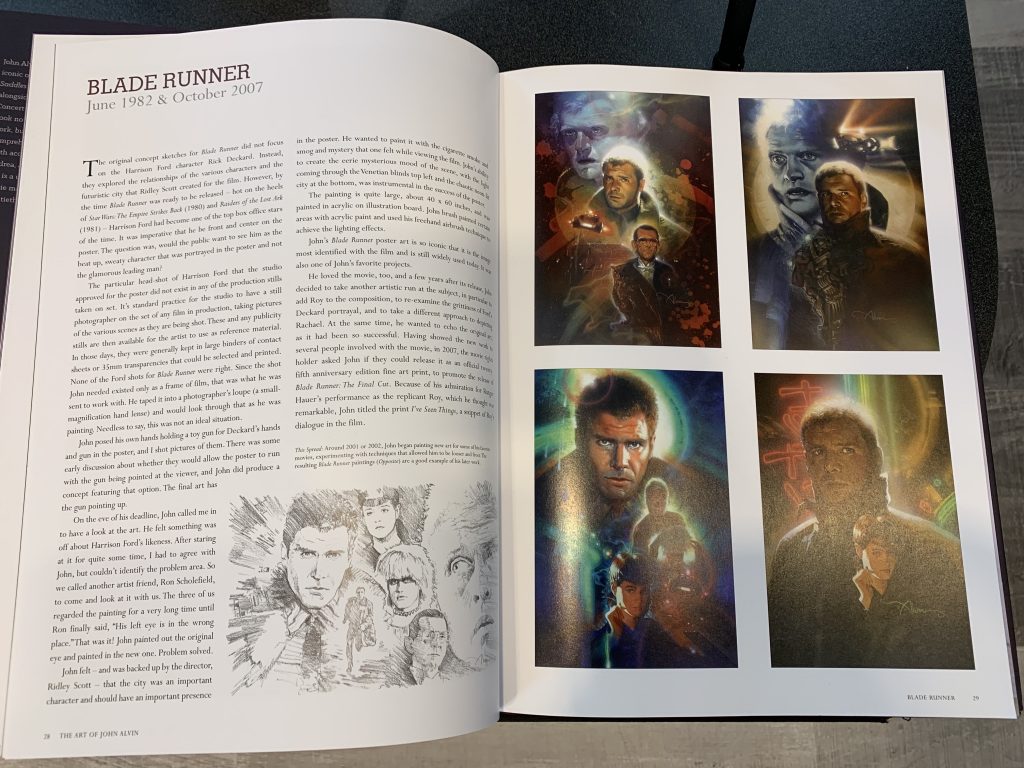

Only four full color John Alvin Blade Runner original paintings were painted later representing Blade Runner. All are shown in the book The Art of John Alvin:

JOHN ALVIN DID VERY LITTLE BLADE RUNNER ART

The world and look in Blade Runner was very much influenced by futuristic architecture, as well as what Ridley Scott called, “medieval meets electronics”. He felt validated in this blend of aesthetics in seeing the harbor in Hong Kong, which had both junks and skyscrapers.

BLACK & PEACH WITH A PURPOSE

Of course another major influence was film noir. As Ridley Scott said, “The hunter falls in love with his quarry.” Rachael is not strictly a traditional femme fatale, though Deckard falling in love with her certainly could lead to his downfall. In John Alvin’s Blade Runner movie poster, the image of her hovers just below Deckard’s gun-filled hands, the smoke of her cigarette drawing the eye to both the lead character and the architecture featured in the poster.

FILM NOIR STYLE SAVES THE DAY

Alvin’s Blade Runner poster is as far off model as he could have gone without losing the spirit of these characters. John Alvin himself talked about that. When he was painting Harrison Ford as Deckard, the only source material he had was a postage stamp-sized image of him in costume. He had to get a jewel’s loop and a magnifying glass to draw him. He determined that utilizing the stylized yet gritty representation so popular in film noir movie posters, with their sharply lit faces and angled light, would be a way of problem-solving or working around the lack of good images of the actors in costume. Even the shards of light in the Blade Runner art are an updated take on the way light was used in the early days promoting film noir.

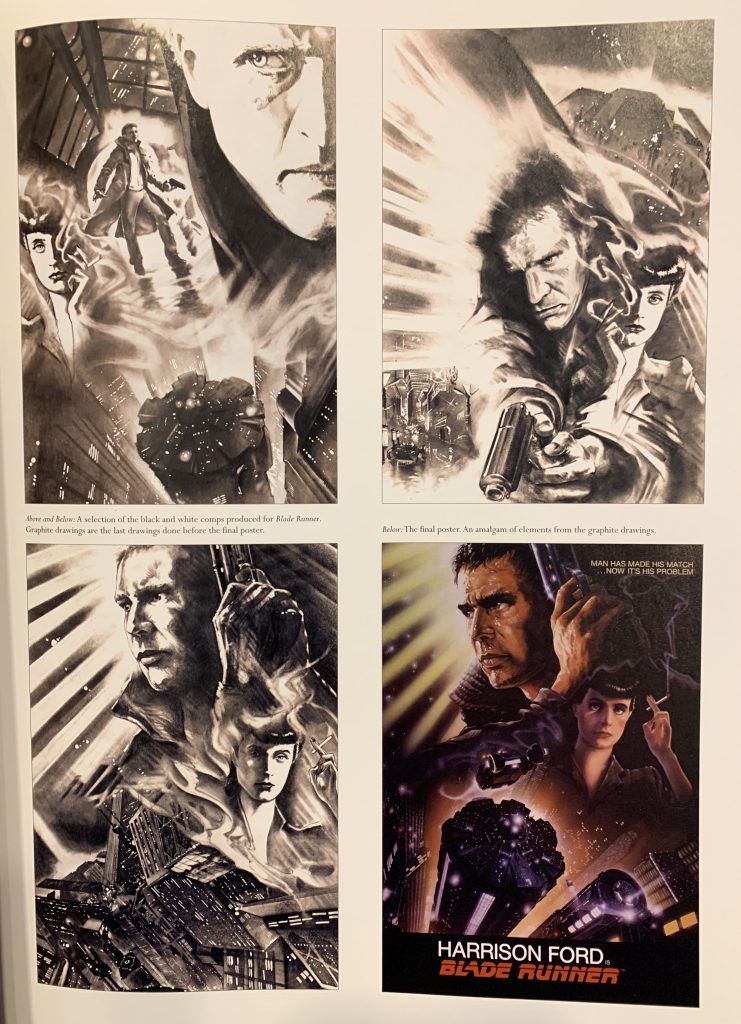

Once the go-ahead from Ridley Scott happened for the John Alvin Blade Runner key art, there were only a few detailed graphites drawn before they chose a finished design. There are often many stages required to get to the final look of a poster. Collectors and fans, no doubt, wish there were more original images. John Alvin wished that, too, since Blade Runner was one of his favorite movies of all time. Though we aren’t 100% sure, we’ve been told people have seen the original art for the poster, and it’s with Ridley Scott. The original art for the 10th anniversary image, which features a much larger Roy Batty in the poster, went at auction over 20 years ago, for almost $100,000, a record for the time.

Once photoshop made traditionally illustrated movie posters largely a thing of the past, John Alvin and his wife Andrea moved to across the country to be nearer to their daughter, who was building a career in theater and around Broadway. He started creating images for the fine art market, and became quickly very much in demand to movie lovers who knew his work and new collectors who were just starting to see the value of illustration art as “real art”, and original movie poster art as an important aspect of film history.

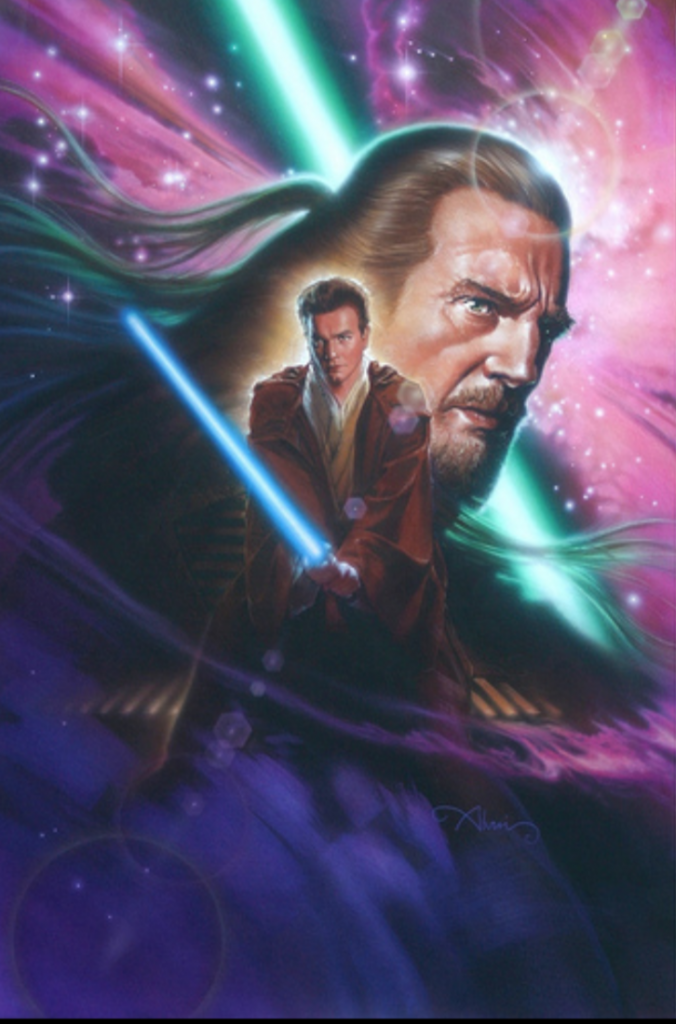

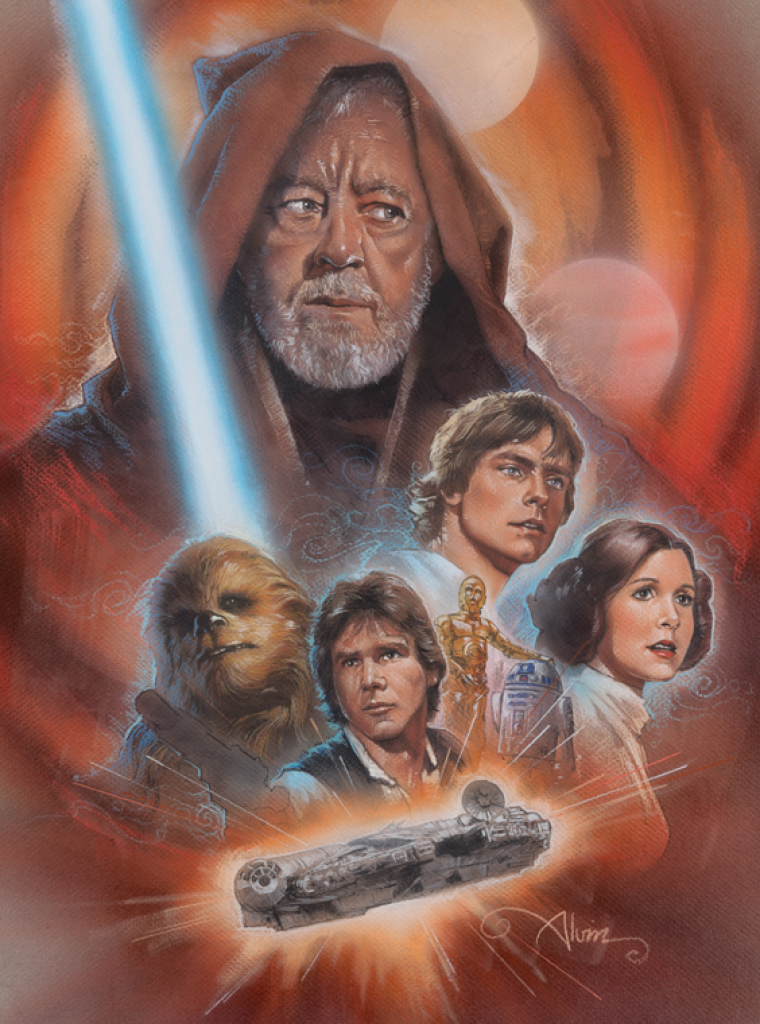

Since George Lucas had been one of his biggest collectors for years, and had commissioned a Star Wars art collection that John entitled, “The Force of Influence”, there were lots of studies for that work that art galleries were able to access and buy to offer to collectors.

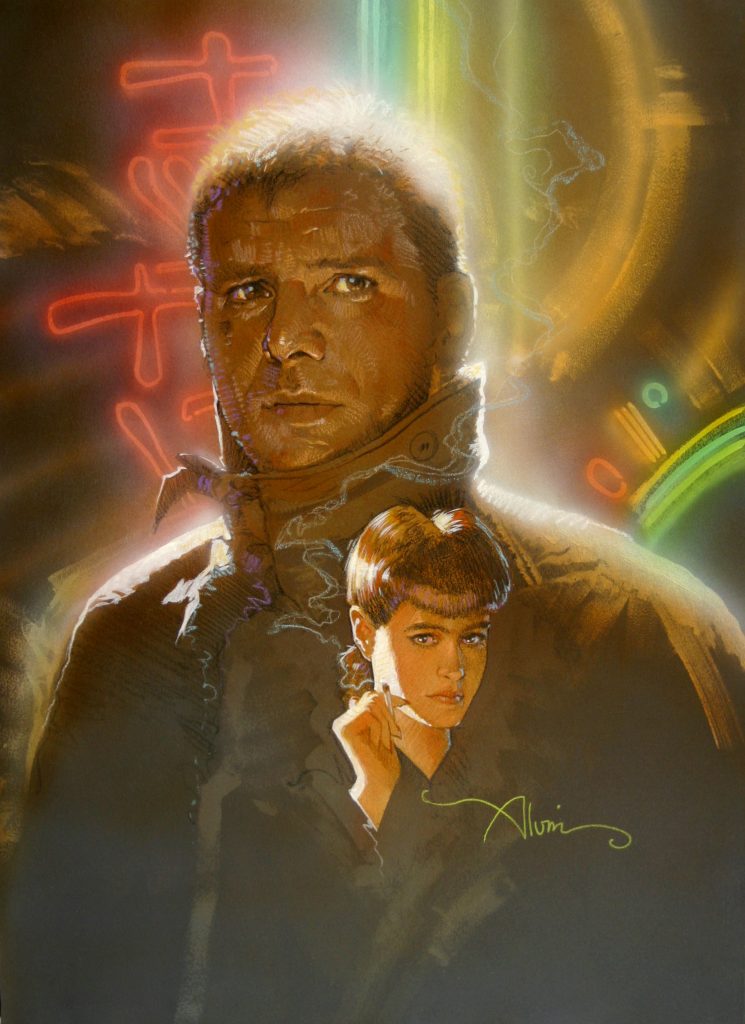

JOHN ALVIN REVISITS A CLASSIC

Blade Runner was a different story. It was only because John loved the film so much that he decided to revisit the film and create a few images to develop ideas he wasn’t able to play with when he worked on the Blade Runner movie poster. One of the things he wanted to do was design a poster image that had Roy Batty as the biggest figure in the art, while still incorporating the architecture. The original Blade Runner art we now have in the gallery on display and for sale includes this piece, and as you can see, John was able to use better source material. This allowed the characters to be more on-model. He wove the architecture into Deckard’s jacket, but also used points of light to draw the eye across one of concept artist Syd Mead’s famous “spinner” crafts so recognizable from the film.

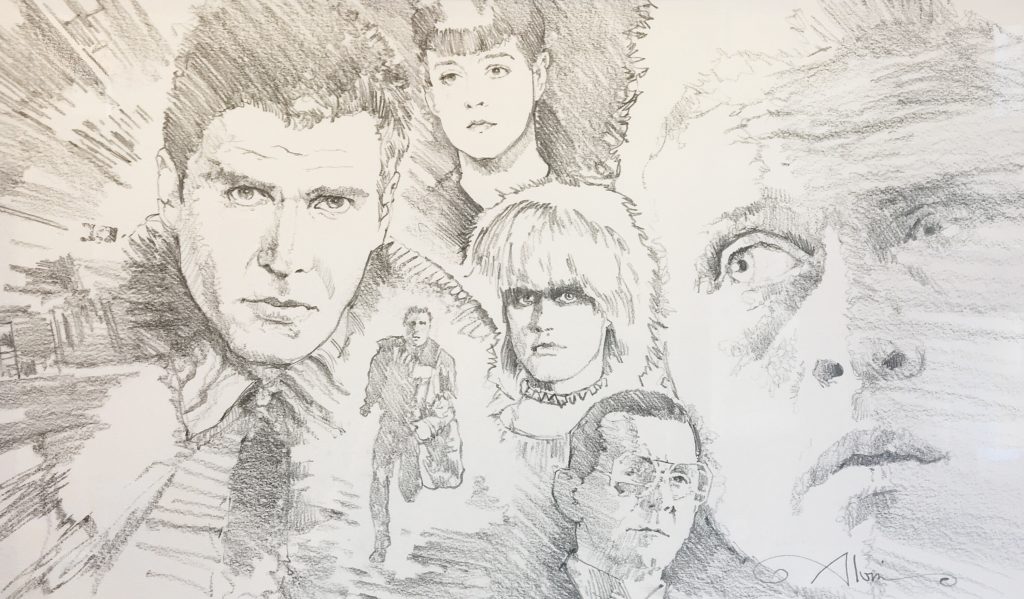

There was also interest on John’s part to create image that included Pris, played by Daryl Hannah, who is not only a fan favorite, but represents a strong female character, albeit a replicant known as a “basic pleasure model”. He also loved the character Eldon Tyrell, who he felt expressed the quality of hubris, especially as he was playing God in experimenting with Rachael in creating her, using memories from his own niece, but not telling her she was a replicant. Alvin saw Tyrell as a tragic figure, and wanted to create an image with Tyrell and his “children”, including Roy Batty, his prodigal son. Unfortunately, he never got a chance to finish this graphite in full color.

In addition to the conflict between Deckard and Batty, John believed the fascination Deckard and Rachael held for each other, though doomed from the start, was one of the aspects of the film that held the story together the most. Much like the film noir plots from the earlier 20th century, he felt their magnetism for each other is part of what made good on what he called the “promise of a great experience”. John always said that’s what he strived to deliver as a movie poster artist.

The love scene from which John Alvin got the name for the below original, called “Kiss Me”, is accompanied by music by the great score created by Vangelis, with the tenor sax solo performed by renowned British musician Dick Morrissey. The plaintive notes on the sax express the mix of idealism and fatalism in their relationship. John Alvin, who loved Vangelis’s score and played his hard-to-get copy of it often, strived to capture that duality. He also believed their story was inseparable from the world they lived in, so he wanted that expressed as well in the art.

The Blade Runner art itself is like all of John Alvin’s original art. It has a way of breaking apart close up and coming together when seen from a distance. Seeing the art in person, it is exciting to be able to dissect how he achieved the emotionally intimate quality for which his illustration art is most well-known. He was someone who did not like to paint in front of others, keeping secrets about how he reached his artistic goals, both big and small. He used any and every tool and medium at his disposal to translate what he had in his mind into physical art. It’s a shame there isn’t more Blade Runner art by John Alvin out there. He passed away over 10 years ago, and even with the release of 2017’s Blade Runner 2049, the 1982 film only becomes more of a classic. Though the film didn’t win a lot of awards, cinephiles did have the good sense to give it a Hugo Award fro Best Dramatic Presentation in 1983. Stop by ArtInsights while the art is still in the gallery to see some of John Alvin’s masterwork. If interested in the only original official Blade Runner piece for sale created by the movie poster artist, CHECK THIS PAGE.

Read an interview with Ridley Scott about Blade Runner

HERE with Harlan Kennedy. HERE with WIRED about a director’s cut.

You can read the original screenplay HERE.