Product Description

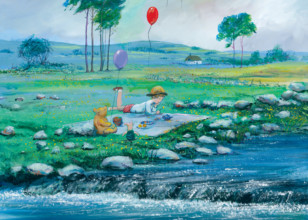

Lying in Wait is created by the father-and-son Disney legends, who collaborated on many beautiful artworks from their impressive body of work.

About Peter and Harrison Ellenshaw:

Peter Ellenshaw was born in 1913 in Essex, England. As a young man, he met the British portrait painter, W. Percy Day, O.B.E. Day was instrumental in developing the highly demanding technique of matte painting, a special effect whereby an object or landscape – a castle, a ship, an island, etc. – is painted on glass and set in front of the camera so that both the real setting and the painting are filmed as one. A few months after their meeting, Ellenshaw became Day’s assistant; and for the next seven years the two artists worked closely together on such epics as Things to Come and The Thief of Baghdad. In 1948, the increasing expense of making films in Hollywood led Walt Disney to England for the production of four live-action adventure films (Treasure Island, The Story of Robin Hood, The Sword and The Rose, and Rob Roy). When Disney met Ellenshaw and became acquainted with his work, his response was immediate and enthusiastic. Here was the man who could re-create in Disney's films the historical England of centuries past and, through matte painting, save the cost of many difficult location shots.

Treasure Island (1950). It was the start of a professional and personal relationship with Walt Disney that was to span nearly three decades. Ellenshaw also brought his artistry to such Disney classics as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Darby O'Gill and the Little People(1959), Mary Poppins (1964) and Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971). In 1954, Ellenshaw created the first full-color painting envisioning Disneyland Park; and he won an Academy Award for special effects for his work on Mary Poppins. In all, he was involved in 34 films for Walt Disney Productions between 1947 and 1979. In 1993, Peter Ellenshaw was named a Disney Legend.

Ellenshaw maintained his identity as a traditional landscape artist during his Disney years and always found time evenings and weekends to work on his own canvases. The relationship to the actual scenes that inspire his paintings is complex. The locations of his paintings are frequently recognizable, but there is never a literal rendering of what one would see there. Ellenshaw says, "This would never work because too much of what one sees is superfluous. In composing a picture, it is necessary to remove the purely accidental and to search for what is significant. Only then does one arrive at the truth."

The son of Peter Ellenshaw, a Disney legend and one of the most respected landscape artists of our time, Harrison grew up with a keen and very traditional sense of color, form and style. A special effects designer, Harrison has memorable credits to his name such as “Star Wars” and “The Empire Strikes Back”. His surprise discovery of the Fauves Art Movement in 1989 turned that all on its head, and the timing of such a revelation couldn’t have been more perfect.

Fauvism was a brief, violently colorful period of artistic rebellion in France led by Henri Matisse. Short-lived (1904-1908) and revolutionary, it packed enough anti-establishment punch to send French art patrons of the day reeling in shock. At the Salon d’Automne in 1905, critics decried the work of the Fauves as “a pot of color flung in the face of the public”. Like punk rock, the actual movement appeared and exploded quickly, but the impression it made changed the course of history. Matisse and the Fauvists implemented the colors of their own unique artistic vision onto canvas, and for maximum effect the pigment was often used straight from the tube. Almost as soon as it began, the Fauves (“wild beast”) movement was over, but their influence paved the way for abstract art.

It was an exhibit of the Fauves work at the Los Angeles County Museum of art in 1989 that proved to be the epiphany for Ellenshaw, and it occurred during the time he was working on the film “Dick Tracy”. As a result, the Fauves’ influence is all over the unforgettable scenery and backgrounds of the movie. More than eighty years after disappearing from the art scene, the Fauves’ romantic, kaleidoscope sensibility had reappeared – this time in Hollywood. Roger Ebert, of The Chicago Sun Times, wrote: “‘Dick Tracy’ is a masterpiece of studio artificiality, of matte drawings and miniatures and optical effects. It creates a world that never could be.”

“Up until this point,” Harrison remembers, “I had been painting trees with black, gray and brown trunks and green leaves, and then I came across the Fauves, and their intense use of color. Their art really touched me. So I began to paint far more colorfully than I had in the past. Today, it’s the color in a painting that brings me the most joy. The great thing is that now with the giclee process of making prints you can match the colors and their intensity perfectly.”

“The Fauves rocked the art world in their day and their legacy deserves revisiting,” says Collectors Editions, Director of Creative Development, Steve Wetzel. “Harrison’s color interpretation of these landscapes is vibrant and intoxicating. It adds such depth to the viewer’s experience when you see these images rendered in such a way.”